When I travelled across Europe, I expected to see history, culture, and food. What I didn’t expect was how much the experience would shape the way I think about mobility.

I explored countries using both cars and regular trains. Driving through European streets gave me one perspective, while travelling by train revealed another. The contrast with North America—and especially with Ontario today—still stays with me.

Cars in Europe: Compact, Efficient, and Secondary

One of the first things I noticed while driving in Europe was how different the cars were. Streets were narrower, parking was harder to find, and cars themselves were smaller. Hatchbacks and small saloons dominated, powered by engines around 1.0 to 1.6 litres.

Fuel was expensive compared to what I was used to, and that alone shaped how people viewed their cars. Vehicles were treated as tools, not status symbols. They were practical, efficient, and often used sparingly—mainly for trips outside cities or in areas not well served by transit.

For most Europeans, the car wasn’t the first choice. It was the back-up.

Trains and Transit: A Seamless Alternative

Using the trains gave me a completely different feeling. They weren’t glamorous, but they were reliable, frequent, and affordable. Whether I was moving between towns or across a region, the train was simply the easiest choice.

I didn’t need to think about parking, traffic, or fuel costs. The trains connected to buses and trams, creating a network where travelling without a car didn’t feel like a limitation—it felt natural.

That’s when I realised something important: strong transit systems change car culture. Where transit works, people choose smaller cars, or none at all, because they don’t need to drive every day.

The Burden of Car Ownership in Ontario

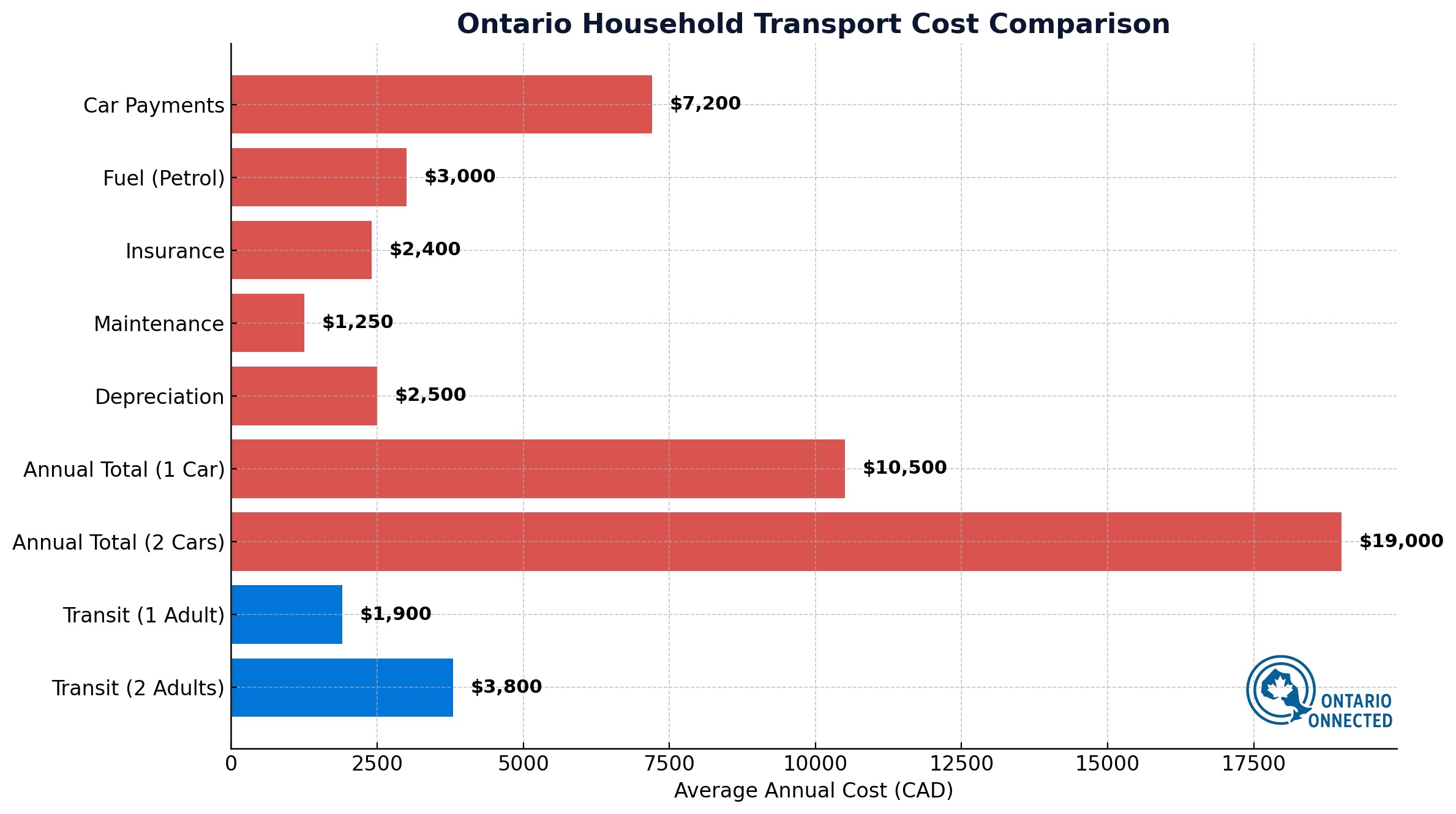

In Ontario, owning a car is not just about the purchase price—it’s the constant stream of costs that drain household budgets. On average:

- Car payments: Around $500–$700 per month for a modest new vehicle.

- Petrol: $200–$300 per month depending on commute distance and fuel prices.

- Insurance: Among the highest in Canada, often $150–$250 per month per car.

- Maintenance and repairs: $1,000–$1,500 per year, more as the vehicle ages.

- Depreciation: Thousands of dollars lost in value every year.

When you add it all up, a single car can easily cost $9,000–$12,000 per year. For families with two cars—a common reality in suburban Ontario—the total can approach $20,000 annually. That’s the equivalent of a second mortgage.

Transit Costs in Comparison

Now compare that with public transit. In Ontario’s major cities, a monthly transit pass ranges from $150–$160 per person. Even if two adults in a household each buy a pass, the yearly cost is roughly $3,500–$4,000 combined.

That’s a fraction of the cost of owning two cars. Even if occasional car rentals or ride-shares are added for special trips, families relying on transit can still save well over $10,000 per year.

For many households, those savings could mean:

- Paying down a mortgage faster

- Saving for children’s education

- Building retirement security

- Simply reducing financial stress

North America: Built Around the Car

Because Ontario’s cities are built around highways rather than rail lines, most families have no choice but to absorb these costs. Larger vehicles dominate the roads—pick-up trucks, SUVs, and saloons with engines 2.5 litres and above. Cars here aren’t just tools; they’re tied to independence and necessity.

But the price of that dependency is heavy. Beyond the financial burden, it also means congestion, lost time, and communities where vast amounts of land are given to parking rather than people.

What Ontario Could Be

Looking back on my European experiences helps me imagine what Ontario could achieve with stronger transit and rail.

Imagine households where a second car—or even the first—becomes optional. Imagine families freeing up thousands of dollars each year because daily commuting can be done by train or bus instead of by car. Imagine cities where parking spaces are replaced by parks, housing, or local shops.

This doesn’t mean eliminating cars. It’s about balance. With modern transit, people would still buy cars—but they’d be smaller, more efficient, and less central to daily life. Families would save money, communities would breathe cleaner air, and Ontario would be a more connected place.

The Lesson I Brought Home

Travelling through Europe taught me a simple truth: car culture is shaped not just by personal preference, but by infrastructure. Where transit is strong, cars become smaller, cheaper, and less dominant. Where transit is weak, cars grow larger, more expensive, and unavoidable.

Ontario now faces a choice. By investing in rail and public transit, we don’t just create a new way to travel. We give families a chance to reshape their finances, reclaim their time, and live in communities designed for people rather than cars.

Having lived here since 2012, I know how deeply car dependency is woven into daily life. But I also know, from experience, that there is another way. Europe showed me what’s possible—now Ontario needs the courage to make it real.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.